Just north of the city limits of Birmingham, Alabama, there is a stretch of highway that has not changed in decades. Google Maps Street View shows me this: the same red brick Wendy’s where my brother and I were once so small we could split a junior cheeseburger (ketchup only), the same church buildings built in the late 80s for a smorgasbord of evangelical denominations, the same shitty strip malls and the Regions bank they remodeled in the 90s and the field where we sometimes saw wild turkeys and the Ridout Funeral Home and the park where they had to tear down the tall metal slide after too many kids broke their arms and busted their heads open. The suburb at the southern end of this stretch of highway was called Jugtown in the late 1800s (and is labeled just “Jug” in an 1898 geologic survey); the “ruburb” at its north end is where I spent most of my childhood.

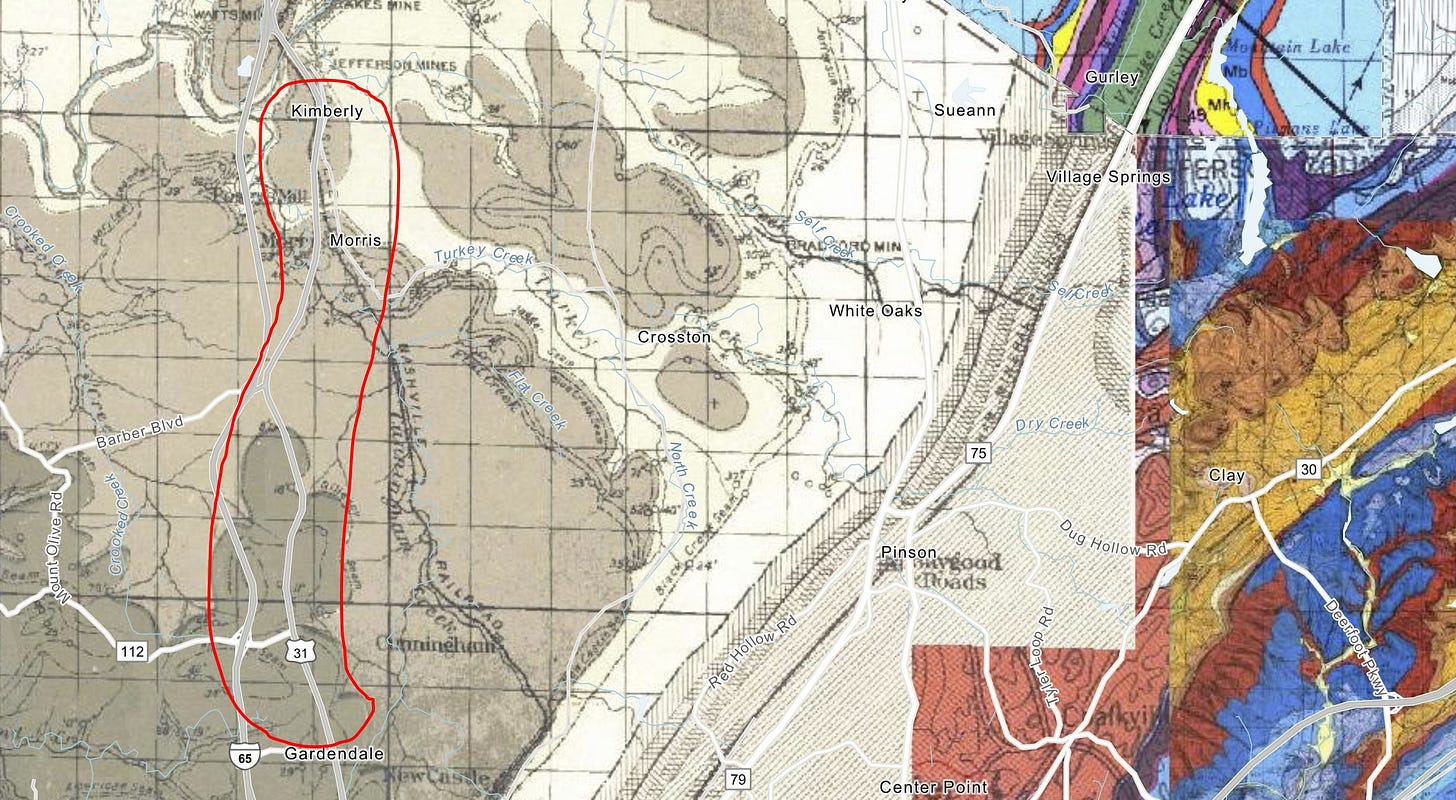

Some of my earliest memories are of this stretch of road, locally known as Decatur Highway and regionally designated Highway 31. We drove it nearly every day from the time I was three until I began kindergarten. Monday through Friday, my mom would drive me and my little brother to the Mt. Vernon Methodist Church preschool, housed in a neo-Gothic cathedralesque building that overlooked The Ravine. In my child’s mind, the church was a towering castle and The Ravine, an undeniably proper noun to me, a gorge as depthless as the legendary Grand Canyon. (A topographic map of the area tells me now that it was only ever around 100 feet deep.) Wednesdays, we drove this stretch of highway again in the evenings to go to our own church for midweek devotional, and drove it twice once more on Sundays for morning and evening services.

I dream frequently of walking along this road, somewhere between our church to the south and our house to the north. I am always heading north.

The first time I remember wondering about rocks was on this stretch of road, too. Across the highway from the Interstate 65 offramp was a roadcut exposing an outcrop of black and grey stone (cliffs to my eyes, although Street View reveals it to be only a dozen feet tall or so). During the winter cold snaps that came more often back then, jagged icicles would snarl over its overhangs like the frozen teeth of an ice dragon.

“Why are the rocks like that?” I remember asking Mom from my car seat in the back of our maroon Dodge minivan.

“Because God made them like that,” she replied.

I remember when the graffiti first appeared on the outcrop, clumsily spray-painted white letters shouting “JESUS SAVES” and further down, the more quiescent “God is Alive.” When the last Google car drove by three months ago, the letters were still just as stark as they were in the mid-90s. Someone must be refreshing the paint. Is it still the same person, all these years later? When these messages first showed up, Mom made a sound of disgust.

“But—isn’t that true?” I asked. We were on our way to church, after all.

“But those rocks are nature,” she said. “And vandalism is tacky, whatever it says.”

I haven’t been back to Alabama since January of 2013, just after graduating college the first time and right before my parents left to settle in Arkansas. In 2015, at age 25, I discovered geology, and the sudden revelation that the question “Why are the rocks like that?” could in fact be answered swept me up in a journey that whisked me across the North American tectonic plate to the comparatively young, volcanic land of western Oregon. Here the streets are lined with a buffet line not of different flavors of Southern Protestantism but discount cannabis dispensaries (which, at least, have to pay taxes). I am mostly happy here in the Willamette Valley, buttressed by the Cascade Mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. The land is beautiful and, after six years in an Earth science PhD program, I know its stories and its names.

Recently, however, I have begun to feel the call of my roots, all tangled up in the daylily bulbs my mom planted in our backyard and the Lick Creek gulch behind my neighborhood where I saw once a river otter after my first breakup. While cross-country plane tickets are expensive, fortunately, Google is free. And what was up with that outcrop on Highway 31? What story did those rocks have to tell?

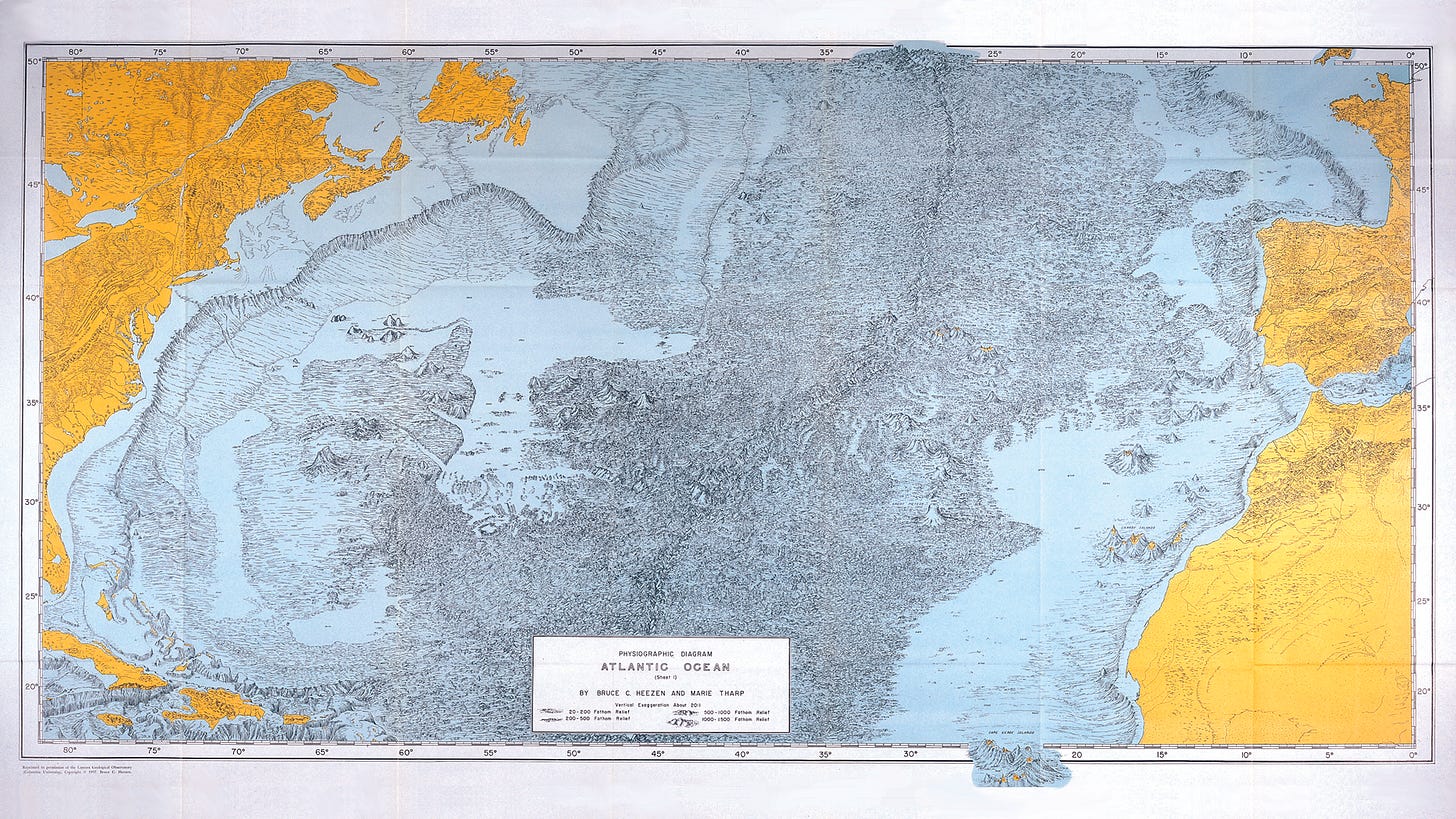

That story is what initially drew me to the geosciences and is also why I keep coming back to it even though I’ve officially left its academic pursuit behind (another story for another time). The magic of being able to look at a rock, a riverbed, a mountain range, a planet and pull together disparate datasets into a coherent narrative about how and why it became itself has never lost its shine for me. I look back at my childhood journeys up and down Highway 31 to preschool, to church, to the library and the skating rink and Ming’s Garden Chinese food to parse out how and why I became myself. Earth scientists collate and synthesize geochemical signals, sonar readings, stratigraphic columns, fossil assemblages, satellite imagery, and a hundred other types of information to tell an ever-shifting story that becomes clearer and more granular as we ask more and better questions with more and better technology.

As is usual for me, I decided that I needed to know the origin story of the Highway 31 outcrop at around 9:30 last night (coincidentally also the approximate time when I usually decide that I need to rearrange the furniture). By a quarter past midnight, I had tracked down the geologic map containing this outcrop, an 1898 accounting of the coal seams that meander through the Black Warrior Basin of north-central Alabama. After identifying the outcropping rock unit as part of the Mary Lee Group of the Pottsville Formation, I tracked down the lithology (rock characteristics) and depositional setting (the kind of environment where the rocks formed) of this group in a 1976 Department of the Interior publication about the nature of the Black Warrior coal beds.

To my surprise, these rocks were actually part of the same orogeny, or mountain-forming event, that formed the Ouachita Mountains in Arkansas where I cut my teeth on geologic history during my post-baccalaureate degree at University of Arkansas at Little Rock. The black shales seen in the pictures above were deposited in the ocean basin that, 290 million years ago, churned between the southern shore of Laurentia (the ancestral North American plate) and the northbound continent of Gondwana. The collision between these two plates thrust the mountain range now known as the Ouachitas over ten thousand feet above sea level. (After nearly 300 million years of erosion, their tallest peak, the Mt. Magazine plateau near my parents’ house in central Arkansas, only reaches just above 2700 feet.) The coal mined by many of the old timers at my childhood church formed from peat bogs that once lined the upland deltaic plains where shale-forming sediment washed off Laurentia’s coast and into the narrowing ocean between it and Gondwana.

Even if I’ve lost you by this point, the important part is that these stories carry a sanctity to me that, despite my most earnest efforts, I could never quite find in the pink-carpeted church auditorium where I spent so many hours of my childhood. (Really though—who was responsible for that Pepto-Bismol carpet shade? Yet another great and terrible mystery.) Ostensibly the answer to that other age-old question, “What do I want to be when I grow up?”, the seven and a half years I spent getting first my Earth science bachelor’s and then my doctorate were, more than anything, a search for the sacred threads that bind us to the vastness of time and space.

I dream of that stretch of Highway 31 often, my feet tracking the cracked asphalt curving gently past the revenant signature of a long-dead ocean fed by long-dead river valleys. Even in sleep, I follow the questions that first germinated in the thoughts of that curly-headed Southern child who still whispers questions at the core of me. I search. I walk. North, north, north.

Some poetry

“An excuse for bad housekeeping”

Dust collects between my bones. Not my bones, but my ostrich skull and otter femur, the mink mandible and deer jaw, the cervical vertebrae of a cow I decorated with bits of sponge, coral, zeolites, displayed on my mantel to make visitors wonder, Is she a naturalist or a witch? (Both?) I really should dust, however I am already dusting, shedding a silent susurration of skin cells, split ends, dandruff when I don’t shampoo enough (often). I can dust, but then I will just dust more, and only have to dust again. (Is this cyclicity civilization?) The dust is me, is cat hair, is husband stuff, is cookie crumbs and garden soil, is the pollen that enlists my body to fight my body. (Stupid grass.) The scientists who study dust (yes, the palynologists, what nerds) tell us that every year, over five thousand tons of space dust find their way to earth’s surface, so surely some finds its way here? What a collection. Perhaps I should not dust, because perhaps the dust belongs on my mantel after all.

Recommendations from my recently read books

The Book of Love by Kelly Link

James by James Percival Everett

Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus

This Is How You Lose the Time War by Amal el-Mohtar and Max Gladstone